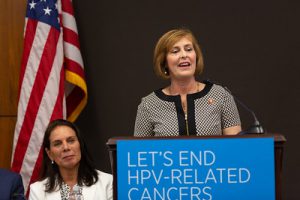

Let’s End HPV-related Cancers: A Congressional Briefing

Every two minutes, a woman somewhere in the world dies of cervical cancer.

That harrowing statistic, shared by Anna R. Giuliano, PhD, founding director of the Center for Immunization and Infection Research in Cancer at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, reflects a great frustration in public health. There is a vaccine that prevents infection with the virus that can cause cervical cancer and several other cancer types, yet worldwide, not enough people are taking advantage of it.

To bring awareness to this issue, on Thursday, several leading cancer organizations held a congressional briefing titled “Let’s End HPV-related Cancers.” The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), Moffitt Cancer Center, and the Biden Cancer Initiative organized the briefing in partnership with American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Association of American Cancer Institutes (AACI), Prevent Cancer Foundation, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC).

Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), as well as many cases of anal, vulvar, penile, vaginal, and head and neck cancers. Globally, 630,000 cases of HPV-related cancers are diagnosed each year, including more than 33,000 HPV-related cancers in the U.S. alone.

In 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first vaccine that prevents HPV infection. The latest and most effective, Gardasil 9, is currently available in the United States.

Today, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all boys and girls receive two doses of the vaccine beginning at age 11 or 12. As of 2017, the last year for which full data are available, 48.6 percent of U.S. adolescents were up-to-date on HPV vaccination. Vaccination rates vary considerably from state to state and across different demographic groups.

The briefing’s honorary congressional cochair, Rep. Kathy Castor (D-Florida), said she became motivated to increase uptake of the HPV vaccine after she learned that Florida had very low vaccination rates compared with other states.

“We have the tools at our disposal to eliminate HPV-related cancers and save lives,” she said.

Gilbert S. Omenn, MD, PhD, chairman of the AACR’s Health Policy Subcommittee and director of the Center for Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics at the University of Michigan, told the audience, “So often when we talk about cancer, we are trying to treat a disease that has already wreaked havoc on the body. Today, we’re talking about prevention.”

To set a tone for the briefing, Giuliano and Omenn wrote an article for STAT, urging global action against HPV-related cancers. The sponsoring organizations also issued a call to action to U.S. policymakers, seeking the following goals domestically:

- Complete vaccination of more than 80 percent of males and females ages 13 to 15 by 2020;

- Screening of 93 percent of age-eligible females for cervical cancer by 2020;

- Providing prompt follow-up and proper treatment of females who screen positive for high-grade precancerous cervical lesions.

Can we eliminate cervical cancer?

Giuliano explained that in public health, “control” refers to reducing incidence of a certain disease to a more moderate level. Cervical cancer offers a rare chance at “elimination” of a cancer, which she described as “getting to near zero in a given area.”

She said multiple countries have vowed to be the first to eliminate this cancer type, and the HPV vaccine is a powerful tool for doing so.

John T. Schiller, PhD, an NIH Distinguished Investigator and deputy chief, Laboratory of Cellular Oncology, Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute, whose research led directly to the development of HPV vaccines, agreed that the vaccine could potentially eliminate cervical cancer, but identified multiple barriers to more widespread use. For one, the vaccine is not as accessible in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) as it is in the United States. He said research is underway to determine whether fewer rounds of the vaccine may be effective, which could make vaccination more convenient in places with limited access to doctors’ offices or clinics.

Vaccination, screening, and treatment all play a role

Two leaders from the CDC discussed some of the ways American families have experienced HPV vaccination and cervical screening efforts. Melinda Wharton, MD, MPH, director of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, noted that research has shown that parents often say they did not get the HPV vaccine for their child because a pediatrician has not specifically recommended it. Other families have said they did not know about the vaccine, didn’t feel it was necessary, or said they believed their child didn’t need it because they were not sexually active. However, research has shown that the vaccine is most effective when administered in early adolescence, before sexual activity begins.

Vicki Benard, PhD, chief of the CDC’s Cancer Surveillance Branch, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, said screening for precancerous conditions will also be important in the effort to eliminate cervical cancer. She said that women who do not get screened for cervical cancer are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages of the disease, when it may be too late for successful treatment.

Benard said many women suffer from racial and socioeconomic disparities surrounding cervical cancer. In the U.S., screening rates vary across socioeconomic groups, and minority women are less likely than white women to be treated according to clinical guidelines.

“We need to develop interventions to get HPV vaccination, and cervical cancer screening and treatment, to all women who need it,” Benard said.

Global disparities affect mortality

That sentiment was echoed on a global scale by Julie S. Torode, PhD, director of Special Projects at the UICC. While many high-income nations have seen incidence stabilize, LMICs have not.

And mortality from cervical cancer remains high; in some lower-income nations, four out of every five women diagnosed will die of the disease, Torode said.

As a result, she explained, the World Health Organization (WHO) has adopted a “life course” approach to global cervical cancer control. They want to see 90 percent of girls fully vaccinated by 15 years of age; 70 percent of women screened for HPV at 35 and 45 years of age; and 90 percent of women who are diagnosed with cervical disease receive appropriate treatment. Although there is much work to be done, some developing nations have undertaken ambitious vaccination programs. Rwanda, for example, has reported HPV vaccination rates of more than 90 percent of eligible girls.

Survivors offer crucial perspective

Jason Mendelsohn’s voice carries easily through a crowded room, belying the throat damage he sustained as he underwent chemotherapy and radiation to treat tonsil cancer.

He was diagnosed in 2014. He was in his early 40s, enjoying life with his young family and believing that he was in perfect health.

Instead, he found himself part of a growing segment of the population: middle-aged men, diagnosed with an oropharyngeal cancer (tongue, tonsils, or throat), related to an HPV infection likely sustained during their younger years.

“I wish the HPV vaccine had existed when I was a young boy,” he said. Although he is in good health today, he suffers lasting effects of his cancer treatment, and has become a passionate advocate for HPV vaccination, reminding the public that the HPV-related cancers affect men in growing numbers.

Tamika Felder was diagnosed with cervical cancer at age 25.

“I am thankful that I didn’t lose my life,” she told the crowd. “But I did lose my fertility.” She has also struggled with lymphedema and bone loss as a result of her treatments.

Felder launched Cervivor, a nonprofit focused on cervical cancer awareness and advocacy. She urged the audience at the briefing to remember that behind all the statistics on HPV-related cancers, there are real people.

“I implore you to do something, because we can do something,” she said.

A video of the entire briefing is available:

HPV is a virus, and any virus left untreated can cause cancer, so individuals should be aware of testing, and prevention, so things can be taken care of before its late.