FDA Rounded out 2018 With Three Oncology Approvals

In the final weeks of 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced three approvals of anticancer therapeutics. These decisions brought the total number of new anticancer therapeutics approved by the FDA in 2018 to 18, a record in recent years. In addition, the agency approved expanding the use of 10 previously approved anticancer therapeutics to include new types of cancer in 2018.

The year-ending oncology approvals were: the December 19 expansion in the use of the immunotherapeutic pembrolizumab (Keytruda) to include treating certain patients with a rare, aggressive type of skin cancer called Merkel cell carcinoma, the December 20 approval of the new anticancer therapeutic calaspargase pegol-mknl (Asparlas) for treating certain patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and the December 21 approval of the new molecularly targeted therapeutic tagraxofusp-erzs (Elzonris) for treating certain patients with a rare type of blood cancer called blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm.

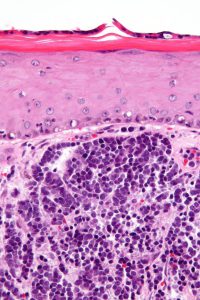

Use of pembrolizumab expanded to Merkel cell carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma gets its name from the cells in which it arises: the cells in the top layer of the skin that are called Merkel cells. Although it is a rare disease, the U.S. Merkel cell carcinoma incidence rate has increased more than four-fold in recent decades, according to data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). In 1986, there were 0.15 new cases of Merkel cell carcinoma per 100,000 U.S. adults. This rose to 0.7 per 100,000 U.S. adults in 2013, which translates to almost 2,500 new cases of the disease in that year.

Overall, the 10-year relative survival rate for Merkel cell carcinoma is estimated to be 57 percent, but it varies by stage of diagnosis. The 10-year relative survival rate for patients diagnosed with early-stage disease is 71 percent but for those diagnosed with metastatic disease it is 20 percent. The outcomes for patients are so poor that it is the second deadliest form of skin cancer after melanoma.

Pembrolizumab was approved for treating adult and pediatric patients with recurrent locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. The approval was based on results from the phase II KEYNOTE-17 clinical trial, which showed that 12 of the 50 patients enrolled in the trial (24 percent) had a complete response and 16 (30 percent) had a partial response. These data are consistent with early results from the trial, which were presented by Paul Ngheim, MD, PhD, at the AACR Annual Meeting 2016.

Pembrolizumab is the second immunotherapeutic to be approved for treating patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. The first was avelumab (Bavencio), which was approved for this use in March 2017.

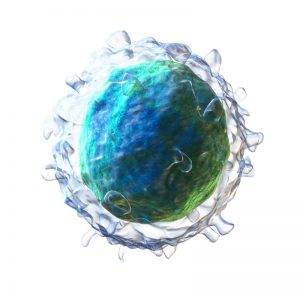

Pembrolizumab and avelumab work in different ways to release a brake called PD-1 on cancer-fighting immune cells called T cells. Pembrolizumab directly targets the PD-1 brake, preventing it from being engaged by two proteins called PD-L1 and PD-L2. In contrast, avelumab targets PD-L1, preventing it from engaging the PD-1 brake. In both cases, because the PD-1 brake is not engaged, the T cells are released to destroy cancer cells.

Because of the way that pembrolizumab and avelumab work, they have relatively broad utility in the treatment of cancer. Pembrolizumab was first approved by the FDA in September 2014, for treating melanoma. Since then, it has been approved for treating nine other types of cancer, including Merkel cell carcinoma, and for treating patients with any type of solid tumor that is characterized by the presence of specific biomarkers known as microsatellite instability–high or mismatch repair–deficient.

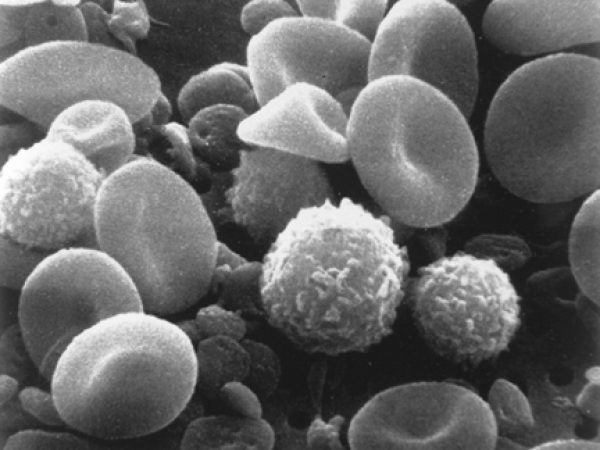

A new treatment for ALL

Each year, almost 6,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with ALL, according to data from the NCI. Fifty five percent of these individuals are children, adolescents, and young adults under the age of 20.

Most people diagnosed with ALL, including children, adolescents, and young adults, are treated with a combination of four, or even five, chemotherapeutics. In most cases, one of the chemotherapeutics in the multiagent treatment works by depleting the patient’s body of L-asparagine, which is one of the building blocks that cells use to create the proteins they need to function. ALL cells are unable to generate their own L-asparagine. Therefore, depletion of this critical building block interferes with the ability of ALL cells to generate proteins and, ultimately, to survive.

Chemotherapeutics that work by depleting L-asparagine are asparagine-specific enzymes. They are isolated from the bacterium Escherichia coli or the bacterium Erwinia carotovora. In many chemotherapeutics, the asparagine-specific enzyme is linked to a molecule called polyethylene glycol forming a pegaspargase. This slows down clearance of the asparagine-specific enzyme from the patient’s body.

In calaspargase pegol-mknl, the linker used to attach the polyethylene glycol to the asparagine-specific enzyme is different from the linkers used in other pegaspargase chemotherapeutics. The new linker is more stable, meaning that it slows down clearance of the asparagine-specific enzyme from a patient’s body further. Early research showed that one dose of calaspargase pegol-mknl depleted L-asparagine from the blood for 18 days, whereas one dose of a standard pegaspargase chemotherapeutic depleted L-asparagine from the blood for only 11 days.

According to the FDA statement, the agency approved calaspargase pegol-mknl because it provided for a longer interval between doses compared with other pegaspargase chemotherapeutics. It is intended for use as part of a multichemotherapeutic treatment regimen for children, adolescents, and young adults ages 1 month to 21 years who have been diagnosed with ALL.

First FDA-approved treatment for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is a rare type of blood cancer that arises in immune cells called plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. It was not until 2016 that researchers and physicians had sufficient understanding of the disease to classify it as a specific medical condition in its own right. From 2008 to 2016, it was classified as a member of the acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and related neoplasms family by the World Health Organization.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is a highly aggressive disease. Most patients are treated with a multichemotherapeutic treatment regimen. This treatment strategy is initially successful for most patients but ultimately fails to keep the disease at bay. The median survival of patients diagnosed with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is just 12 to 14 months, according to the NCI.

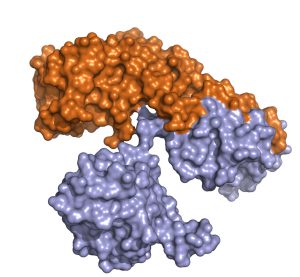

Research has shown that the cancerous blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm cells have high levels of a protein called CD123 on their surface. This led researchers to investigate whether targeting CD123 could provide a new approach to treating patients with this disease.

Tagraxofusp-erzs, which was known as SL-401 during its development, targets CD123. It is a molecularly targeted cytotoxin because it comprises a CD123-targeting portion linked to the parts of the diphtheria toxin that cause cell death. Once the CD123-targeting portion attaches to CD123 on the surface of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm cells, the therapeutic is internalized by the cell where the diphtheria toxin portion is released and causes the cancerous cell to die.

Tagraxofusp-erzs was approved for treating all patients with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm who are age 2 or older after it was shown in an early-stage clinical trial that seven of 13 patients (53.8 percent) with previously untreated blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm who received the new molecularly targeted cytotoxin had a complete response or a clinical complete response (defined as a complete response with residual skin abnormality not indicative of active disease), according to the statement from the FDA. In addition, one of 15 patients with relapsed or refractory blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm had a complete response and one had a clinical complete response.

With this approval, tagraxofusp-erzs became the first treatment approved specifically for treating patients with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. The molecularly targeted cytotoxin is being tested in several other clinical trials as a potential treatment for other types of cancer that have high levels of CD123, including chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.

Looking to more progress in 2019

Given that research is a continuous endeavor that perpetually deepens our understanding of the biology of cancer, we expect that in 2019 we will see many more new anticancer therapeutics approved by the FDA and many previously approved anticancer therapeutics have their use expanded to include new types of cancer. We look forward to keeping you up to date with the progress being made against cancer.