Recent Advances in Treating Ovarian Cancer

A pair of studies published recently in the AACR’s journal Clinical Cancer Research report on some interesting observations and developments in treating ovarian cancer, a difficult-to-diagnose and difficult-to-treat disease.

In one study, researchers reported on a new imaging system that can guide surgeons in real-time to remove additional tumors in ovarian cancer patients that are not visible or could not be felt during standard surgical procedure. In the other study, researchers made an interesting observation that chemotherapy given prior to surgery causes specific alterations to the ovarian cancer patients’ immune cells. Because of this, the authors speculate that immunotherapy given to these patients right after chemo may help prevent the cancer from coming back.

Filling an unmet need

This year in the United States, about 22,280 women are estimated to receive a new diagnosis of ovarian cancer and about 14,240 women are expected to die from this disease. The 5-year survival for early-stage ovarian cancer is 92.1 percent, but only 14.8 percent of ovarian cancers are diagnosed at an early stage. Because we still do not have good tests to detect the disease early, most patients are diagnosed with advanced disease, and even with extensive surgery and chemotherapy, most patients experience a relapse. Given these challenges, research like that reported in these two studies to identify new methods and opportunities to improve the treatment of ovarian cancer is much needed.

An imaging system that can guide surgeons to remove more ovarian cancer

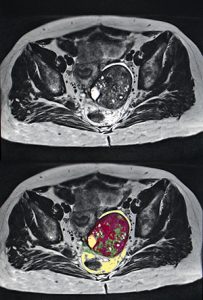

A team of researchers from Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands and Purdue University in the United States developed a tumor-specific fluorescent agent and a dedicated imaging system to detect tumors in real-time during a surgical procedure for ovarian cancer called cytoreduction. This surgical procedure, also known as debulking surgery, is commonly performed in advanced ovarian cancer cases in order to remove as much of the tumor as possible. The imaging system can help resect additional tumor lesions that are not visible to the surgeons’ naked eyes.

“Surgery is the most important treatment for ovarian cancer, and surgeons mainly have to rely on their naked eyes to identify tumor tissue, which is not optimal,” said study author Alexander L. Vahrmeijer MD, PhD, head of the Image-guided Surgery group in the Department of Surgery at Leiden University Medical Center, in an interview. “Near infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging is a novel technique that may assist the surgeons to improve visualization of tumors during surgery,” he added.

The team developed a new fluorescent agent, OTL38, which is a conjugate of NIR fluorescent dye and a folate analog that binds to folate receptor-alpha (FRα), and studied the agent for the first time in humans. According to Vahrmeijer, FRα is expressed in more than 90 percent of ovarian cancers but in relatively low levels in some normal tissues.

“The main advantage of NIR light is that it can penetrate tissue in the order of centimeters, allowing the surgeon to visualize tumors underneath the tissue surface that can be detected using a dedicated imaging system,” he explained.

The researchers tested the imaging system in 12 patients with ovarian cancer and found that OTL38 accumulated in FRα-positive tumors and metastases, and enabled the surgeons to remove an additional 29 percent of malignant tissue (confirmed by pathological examination of the resected tumors) that could not be identified with naked eyes and/or palpation.

“It is reasonably plausible to assume that if more cancer is removed the survival will be better,” Vahrmeijer said. “Although more research is needed, this is hopefully the first step toward improving the surgical outcome [for ovarian] cancer patients.”

Can presurgery chemotherapy make advanced ovarian cancers responsive to immunotherapy?

Research conducted in the past using mice suggests that when chemotherapy destroys cancer cells, it also stimulates immune cells in the cancer that can kill cancer cells, explained Frances R. Balkwill, PhD, professor of cancer biology at Barts Cancer Institute in Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom, and senior author of another study. “We wanted to study whether this was also true in cancer patients, and whether it occurred with the chemotherapy used to treat women with ovarian cancer,” she added.

Balkwill and colleagues collected pre- and post-chemotherapy biopsies and blood samples from 54 patients with advanced-stage high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC) who underwent platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and from six patients who underwent surgery without prior chemotherapy.

HGSC is a type of ovarian cancer that is quite difficult to treat because it is often detected after it has spread quite extensively in the body; and although the disease can respond well to the first chemotherapy treatments, it often relapses and becomes more difficult to treat, Balkwill said.

The researchers analyzed the samples using immunohistochemistry and RNA sequencing to study the changes in the tumor immune microenvironment with chemotherapy.

They found that in patients who received chemotherapy, there was evidence of activation of certain types of T cells that can fight cancer cells, while the number of a type of T cell that suppresses the immune system decreased. The results were more pronounced in those who had a good response to chemotherapy, compared with those who had a poor response to chemotherapy.

“Our research provides evidence that immunotherapy may be more effective if given straight after chemotherapy,” Balkwill said.

“Although we found that chemotherapy activated the T cells, the levels of the protein PD-L1 [to which the immune checkpoint molecule PD-1 binds to disable T cells and prevent them from recognizing and destroying the cancer cells] remained the same or increased. However, immune checkpoint blockade therapies [such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab] can stop this from happening, so we suggest that immune checkpoint blockade might be a suitable form of immunotherapy to give to ovarian cancer patients after chemotherapy,” she added.

I hope that these measures work to improve the cure rate.