Can We Treat Colorectal Cancer With Immunotherapy?

March is Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month. About 134,490 people are estimated to be diagnosed with and about 49,190 are expected to die from colorectal cancer in the United States this year. On this blog, you will find several posts that review the challenges and opportunities with screening for colorectal cancer, provide expert opinion on the progress made so far in addressing the challenges, and discuss new research and treatment options that signify progress being made against this disease.

In this post, let’s look at some recent studies that explore the possibility of using immunotherapy to treat colorectal cancer.

Immunotherapy approaches to treat cancers have, in recent years, yielded varying degrees of success. One factor that seems to influence the outcome is the immunogenicity of the cancers against which an immunotherapeutic is being tested. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy, work by releasing the PD-1 “brake” present on T cells. By preventing the PD-1 protein from engaging PD-L1, a protein present mainly on tumor cells, these immunotherapeutics suppress the immune-inhibiting signals transmitted to T cells. The FDA has so far approved immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat certain melanomas, lung cancers, and kidney cancers.

But can we treat colon cancers with immune checkpoint inhibitors?

About five percent of all colorectal cancers are caused by a heritable mutation. Hereditary colorectal cancers, and about 15 percent of sporadic (nonhereditary) colorectal cancers, are known to have increased mutational load due to DNA mismatch-repair deficiencies. One hypothesis is that tumors that have a high mutational load are likely to be susceptible to immunotherapeutic targeting, because such tumors stimulate the immune system.

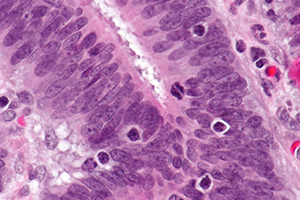

A paper and accompanying commentary published in Cancer Discovery last year explain how the immune microenvironment of colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability (MSI), a marker of mutations in DNA mismatch-repair genes, might make them good candidates for immune checkpoint inhibition. The study found that MSI tumors are highly infiltrated with activated CD8-positive cytotoxic T cell lymphocytes. However, MSI tumors also had high levels of inhibitory immune checkpoint proteins, including PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, and LAG-3, which meant that the infiltrating immune cells were prevented from eliminating the tumors.

Micrograph showing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a case of colorectal cancer with evidence of MSI-H on immunostaining.

The immune checkpoint proteins found in MSI tumors described in the Cancer Discovery paper—PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, and LAG-3,—are all targets of immune checkpoint inhibitors being developed, tested, or that have been approved by the FDA. For example, pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) target PD-1, and ipilimumab (Yervoy) targets CTLA-4.

A multi-institutional team of investigators hypothesized that DNA mismatch repair–deficient tumors are likely to be more responsive to PD-1 blockade than tumors that do not have mismatch-repair deficiencies, and tested their hypothesis in a phase II clinical trial in a small group of patients. Results of this trial, published last year in The New England Journal of Medicine, proved their hypothesis right: Patients with mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer had better clinical response to PD-1 blockade by pembrolizumab than those whose colorectal cancers did not have mismatch-repair deficiencies.

A different approach

A study published in Clinical Cancer Research last week investigated an entirely different approach to making metastatic colorectal cancers responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

In this study, a collaborative team of investigators from the University of Pittsburgh and the Soochow University in China found that a procedure used to treat liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer, called radiofrequency ablation (RFA), could induce antitumor immune responses. They also found that mice treated with a combination of RFA and an immune checkpoint inhibitor survived longer than those treated with either one of the two therapies.

For patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, if liver metastasis is predominant and if the symptoms of their primary colon cancer are easy to manage, resection of liver metastasis prior to treating their colon cancer (liver-first approach) is considered the best option, explained study author Binfeng Lu, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh. For these patients, RFA, a procedure that uses electrical energy to destroy cancer cells, is recommended as an alternative to surgery of the liver metastases, especially if the liver nodules are small.

Therefore, the researchers asked: can RFA make colorectal cancers immunogenic?

To find an answer to their question, Lu and colleagues analyzed colorectal tumor samples collected from a group of patients who received RFA of liver metastasis before their colorectal tumors were treated, and another group who had their colorectal cancers treated first.

The researchers found that in patients whose liver metastases were treated with RFA first, there was an increase in the infiltration of T cells in their colon tumors. They also found that these tumors had increased levels of the immune-inhibitory molecule PD-L1 in their tumor cells and in immune cells within the tumor.

“These properties of RFA suggest it can potentially be used to make colorectal cancer patients who are nonresponsive to PD-1-based immunotherapy become responsive,” Lu said.

The researchers then conducted experiments in mice and found that an anti-PD-1 antibody was effective in inhibiting the RFA-induced PD-L1 upregulation in mice bearing human colon tumors, and a combination of RFA and PD-1 blockade was more potent than RFA or PD-1 blockade tested individually. The investigators are planning to initiate a phase I clinical trial to evaluate whether combining RFA with an anti-PD-1 antibody immunotherapy will benefit patients with colorectal cancer who have liver metastases.

As surgical oncologist and immunotherapy expert Suzanne Topalian, MD, predicted in a blog post earlier this year, researchers continue to gain a lot more knowledge and a deeper understanding of how the immune pathways work so that immunotherapy can be extended to more cancer types.

The AACR is hosting a conference entitled “Colorectal Cancer: From Initiation to Outcomes” Sept. 17-20, 2016, in Tampa, Florida. The deadline to submit abstracts for this conference is July 11, 2016.