As Parents Consider the HPV Vaccine, the Message Matters

In examination rooms all around the country, a big decision turns on a single moment.

A pediatrician tells a parent that his or her adolescent should be vaccinated against the human papillomavirus (HPV). Some parents have already made their choice. Others will decide on the spot.

A study published last week in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention (CEBP), a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, showed that the words the physician uses may have a strong influence on that decision.

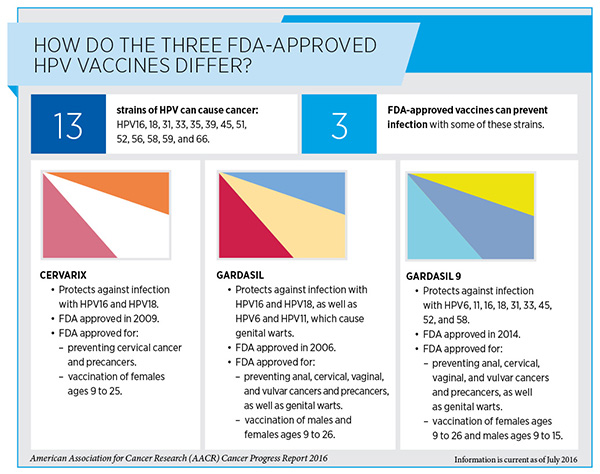

HPV causes most cases of cervical cancer and a large proportion of vaginal, vulvar, anal, and penile cancers. It is also a risk factor for oropharyngeal cancers. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that boys and girls receive the three-dose HPV vaccination beginning at age 11 or 12. However, as of 2015, only 42 percent of girls and 28 percent of boys ages 13 to 17 had completed the HPV vaccine series, according to CDC statistics.

In February, the nation’s 69 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers released a consensus statement that called the low HPV vaccination rates a “serious public health threat.” Researchers believe there are many reasons for the low uptake, but one major factor is that physicians don’t always recommend the vaccine at the right time or in the full three doses, according to a study published in CEBP in October 2015.

In the study published last week, Teri L. Malo, a postdoctoral research associate at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, set out to evaluate whether the specific language used by physicians would influence parents’ decisions, and whether physicians would be more likely to use specific messages.

Malo and colleagues tested 15 messages with 1,504 parents of adolescents ages 11-17 and 776 primary care physicians. Nine of the messages were previously approved by the CDC. Malo and her team developed six additional messages.

The most persuasive, with 65 percent of parents and 69 percent of physicians endorsing it, was: “I strongly believe in the importance of this cancer-preventing vaccine for [child’s name].”

Malo was surprised to discover that even parents who told the researchers that they were considering not having their children vaccinated against HPV said they could be persuaded by some of the messages. For example, 59 percent of parents said they would be persuaded by hearing: “[Child’s name] can get [anal/cervical cancer] as an adult, but you can stop that right now. The HPV vaccine prevents most [anal/cervical cancers].”

Most of the 15 messages tested in the study were effective with at least half the parents. The least effective, which only 9 percent of parents said would persuade them to have their children vaccinated: “Would you wait until [child’s name] is in a car accident before you tell [him/her] to wear a seatbelt?”

Malo said the study results indicate that physicians should talk to parents extensively enough to understand their concerns, and perhaps tailor their messages to address those specific worries.

“It’s important to understand what drives parents’ hesitation so that we can help improve provider communication to decrease hesitancy about HPV vaccine,” she said.

The HPV vaccine and school-entry requirements

Malo’s study closely followed some interesting HPV vaccine research by one of her colleagues, William A. Calo, PhD, JD, a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of Health Policy and Management at Gillings.

Calo found that parents are more likely to support laws that would make the HPV vaccine mandatory for school entry if their state offers opt-out provisions, but he was quick to caution that such provisions may weaken the effectiveness of the vaccine requirements.

School-entry requirements have contributed to high uptake rates for vaccinations such as Hepatitis B, Tdap, and MMR, Calo said. Since 2006, half of U.S. state legislatures have introduced measures to add HPV to the list of required vaccines, however, most measures were rejected, often due to parental disapproval or ethical, political, or legal concerns, Calo said. Presently, only Virginia, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia require the HPV vaccine for school enrollment, and all allow parents to opt out.

In order to evaluate parental support for making the HPV vaccine mandatory for school entry, Calo and colleagues, including Noel Brewer, PhD, the study’s senior author, professor of health behavior at the University of North Carolina, and a member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, conducted a web-based survey of 1,501 parents of adolescents between November 2014 and January 2015.

The survey stated, “Some states are trying to pass laws that would require all 11- and 12-year-olds to get HPV vaccine before they are allowed to start sixth grade.” Parents were then asked whether they agreed with the statement, “I think these laws are a good idea.” Overall, 21 percent of parents agreed that such laws are a good idea, and 54 percent disagreed.

Respondents who said they disagreed then received this follow-up statement: “It is okay to have these laws only if parents can opt out when they want to.” When the opt-out provision was added, 57 percent of respondents agreed that the school-entry requirements are a good idea, and 21 percent disagreed.

Calo cautioned that opt-out provisions could weaken the overall effectiveness of vaccination if large numbers of families opted out. He recommended that any states considering opt-out provisions should make sure that parents receive information about the vaccine and that physicians continue to encourage parents to vaccinate their children.

“HPV vaccination saves lives,” Calo said. “We have an unprecedented opportunity to prevent thousands of HPV-associated cancers through vaccination and unfortunately, we are missing that opportunity.”

An AACR Distinguished Lecturer Adds Her Voice

Many physicians, researchers, and policymakers have raised similar calls to action. Earlier this year, Electra D. Paskett, PhD, Marion N. Rowley Professor of Cancer Research and associate director of Population Sciences at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, wrote a column encouraging parents to consider their role in potentially preventing HPV-related cancers.

Paskett, who received the 2015 American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Distinguished Lecture on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities, funded by Susan G. Komen, wrote, “Every parent should ask the question: ‘If there was a vaccine I could give my child that would prevent them from developing six different cancers, would I give it to them?’ The answer would be a resounding yes, and we would have dramatic decrease in HPV-related cancers across the globe.

“A cancer vaccine exists; now people have to use it,” Paskett urged.

nice article i just love this. so much information as well. keep providing us good things.